Fate loves a number. On April 14, 1865, Lincoln was shot. On April 14, 1912, the Titanic struck a large iceberg. On April 14, 1950, Kevin was born to Allan and June Clark.

Fate loves a number. On April 14, 1865, Lincoln was shot. On April 14, 1912, the Titanic struck a large iceberg. On April 14, 1950, Kevin was born to Allan and June Clark.

The Clarks were devoted Catholics from the Bronx. An English major enamored with the novels of Jack London, Allan graduated from Notre Dame. June graduated from Fordham with a history degree and an interest in politics.

When Kevin was five, the family moved from Stuyvesant Town in lower Manhattan to New Jersey. Woods and poison ivy replaced asphalt and sandboxes. Kevin attended St. Andrew’s Grammar School in Westwood and St. Joseph Regional High School in Montvale.

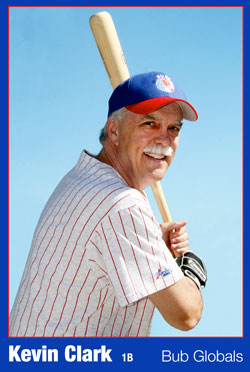

Raised to be readers and athletes, Kevin and his brother Glenn played baseball throughout childhood, performing well on Little League and Babe Ruth teams coached by their father. Southpaw Kevin played centerfield for his freshman high school baseball team, and he even pitched a couple of times. Practitioner of the hanging curve, he once gave up a homerun that still circles the globe twice daily. With wrists thin as tin at fifteen, he couldn’t turn on the inside fastball.

Kevin eventually devoted himself to track, whereupon he was once lapped by the high school phenom Marty Liquori. Never one to let humiliation linger, he was selected All County in both cross-country and the mile during his junior and senior years.

As referenced in several of his poems, Kevin’s genial, open-hearted father, Allan—a quick-handed ballplayer and journalist-turned–public-relations man—died of an aneurism in 1965. His mother would live another thirty-four years. From high school on, Joe Ryan, the jock priest who had played quarterback at St. Peter’s High School in Jersey City and admired the realpolitiks of Bobby Kennedy, became Kevin’s tough-talking metaphysical advisor. He gave him his first single-author volumes of Frost, Thomas, Auden, and Eliot. All remain on his bookshelves.

After Allan’s death, June returned to college, earned two degrees, and became a history teacher and high school counselor. She later changed careers and went on to win election to the board of supervisors by the highest plurality in the history of Bergen County, New Jersey. Five months before his father died, Kevin’s paternal uncle Warren died as well.

Kevin’s aunt, the soon-to-be suspense writer Mary Higgins Clark, supported her five children by commuting to New York to write radio scripts. She regularly took time to encourage Kevin on his writerly path. She also hosted raucous meals that featured family mythologizing, gut-punching laughs, and competitive storytelling—all of which formed a dinnertime school for narrative improvisation from which Kevin and his cousin, the detective writer Carol Higgins Clark, drew lessons.

Penning a column called “Off the Cuff” for his Catholic high school newspaper, Kevin was occasionally called into the vice principal’s office for ideological monitoring. He also reported on track and cross country, covertly supplied wise remarks as captions for yearbook photos, and was a poetry and fiction contributor to the literary magazine. While evidence of Kevin’s high school editorializing is apparently extant in select attics of the land, he’s relieved the maw of history permanently swallowed the literary magazine. No copies exist, he’s certain. Kevin learned much in high school from literature, sports, and two close friends—Frank Dinoia modeled deadpan comic timing while Brian D’Arcy perfected the wry swear word. Along with college buddy Ken Goldberg, master of existential logic and lament, these guys are the backstory denizens of many of his poems.

Robbed at blade’s edge during a track meet at Franklin Field, Kevin rejected an offer to run for the University of Pennsylvania. As the counterculture peaked, Kevin arrived at the University of Florida on a track scholarship. Cutoffs and bare feet replaced Bermudas and penny loafers. Though he medaled a few times, track was a memory by Christmas.

Poetry and politics replaced Catholicism. A ready participant in civil rights and anti-war demonstrations, Kevin was fully immersed in the college life of the sixties and early seventies. He worked as a waiter, cashier, survey rodman, and a short-order barbecue cook. As an undergraduate, he was encouraged in verse-writing by poet and Joyce scholar Brandon Kershner. Kevin graduated and then stayed at Florida in a new MA program for creative writing, where he was steamrolled in succession by poets John Fredrick Nims, John Ciardi, and James Dickey.

Shaken but game, Kevin returned to New Jersey to live near his family. In the summer of 1973 while driving a mud-green Bel Aire, he tore out on the requisite countercultural 8,000-mile cross-country circuit, stopping just long enough to be seduced by the art theatres, bookstores, and head shops of Berkeley. Though he promised his family he’d live in Jersey for a while, after a couple of years of teaching GED at the Adult Learning Center in Hackensack and voracious, chaotic reading across genres, Kevin returned to the Bay Area, where he nurtured a ponytail, played pick-up basketball, sold hi-fi, and consumed poems in the aisles of Moe’s and Cody’s bookstores. In 1977, by an unnervingly close vote of the graduate committee, Kevin was admitted to the UC Davis MA program in poetry writing. It was here that he met lifelong friend and essayist Brad Comann as well as poets Hannah Stein and Wendy Barker, both of The Bolinas Salon.

Though learning a good deal from Karl Shapiro, Thom Gunn, and Ruth Stone at Davis, Kevin serendipitously fell under the tutelage of Sandra Gilbert, who provided an influential array of poets to read, ranging from Pablo Neruda to Sylvia Plath to Ruth Stone herself. Challenging, humorous, and supportive, Sandra regularly chanted this writer’s mantra for her students, “Keep the seat of the pants in the seat of the chair.” She always urged her students to have “an envelope ready to send out the poems if they come back.” Kevin finds himself continually stealing these lines for his own students. Since playing for the St. Louis Cardinals was apparently out of the question, he finds no greater vocational thrill than watching his poetry students find their voices.

Single, lyric-minded, unpublished, and not a little testosteronic, Kevin went to a friend’s party in December 1980. Across a smoky kitchen filled with young writers, anthro students, and eco-activists, he saw an ur-California woman in a plaid flannel shirt. A sharp-witted Smith graduate who seemed a cross between an intellectual hippie and a park ranger, Amy Hewes smiled at him. Kevin had discovered a woman possessed of inimitable grace leavened by a distinctly Jersey style of comic relief. Amy and Kevin have been together since, marrying on an almond ranch in Esparto, California, in 1983.

Kevin graduated with an MA in creative writing in 1979. A professor in the English Department told him that even if he had a doctorate in English, he would never find a teaching job in the shrinking market. Since Kevin loved the life of writing, reading, and teaching, he enrolled in the Davis PhD program. He claims the classes, the written exams, the oral exams, and the dissertation were easy enough—but the language exams in Italian and Spanish almost sent him off to pursue a career in sports radio. The university coughed up its ounce of mercy, and Kevin passed each on the third try.

In 1985, he and Amy visited Florence, Italy, where he taught modern poetry and wrote his dissertation about the contemporary long poem. There, they regularly scraped up enough lira to drink coffee and chianti with the poet Ralph Black, formerly director of the Brockport Writers Forum, and Stein scholar Jane Bowers, retired provost of John Jay College.

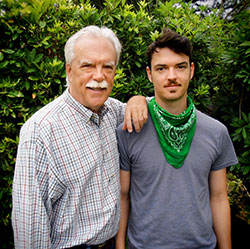

In 1987, son Joe was born, and in 1988 Kevin began a tenure track job teaching literature and creative writing at Cal Poly in San Luis Obispo. (Later, in 2006, Stan Rubin and Judith Kitchen would hire him to teach during summers with the inspiring colleagues at the Rainier Writers Workshop in Tacoma.) Soon after arriving in San Luis Obispo, his new friend, the fiction writer Al Landwehr, invited him into a writing group that continues to give him no-holds-barred advice, as do other keen-eyed veteran writers far and wide, especially old graduate school friend, the award-winning poet Wendy Barker, whose exquisite posthumous Complete Poems is available from LSU Press.

In 1987, son Joe was born, and in 1988 Kevin began a tenure track job teaching literature and creative writing at Cal Poly in San Luis Obispo. (Later, in 2006, Stan Rubin and Judith Kitchen would hire him to teach during summers with the inspiring colleagues at the Rainier Writers Workshop in Tacoma.) Soon after arriving in San Luis Obispo, his new friend, the fiction writer Al Landwehr, invited him into a writing group that continues to give him no-holds-barred advice, as do other keen-eyed veteran writers far and wide, especially old graduate school friend, the award-winning poet Wendy Barker, whose exquisite posthumous Complete Poems is available from LSU Press.

In 1991, daughter Hannah was born, and Kevin was granted tenure. In the footsteps of his father, Kevin coached both of his children in city sports. At fifty-eight years old, he joined his brother and three cousins to snare a championship in the National Adult Baseball Association over-fifty fast-pitch hardball tournament in Arizona.

In the summer of 2001, Kevin achieved familial satori walking across the Venetian peninsula with Amy, Joe, and Hannah. His first full-length collection, In the Evening of No Warning, was published the next year and dedicated to Amy; his second, Self-Portrait with Expletives, was published in 2010 and dedicated to Joe and Hannah. His chapbook The Wanting soon appeared, rendering the imagined life of a scarred Vietnam vet. In 2021, his third full volume of poems, The Consecrations, was published by Stephen F. Austin University Press.

In the summer of 2001, Kevin achieved familial satori walking across the Venetian peninsula with Amy, Joe, and Hannah. His first full-length collection, In the Evening of No Warning, was published the next year and dedicated to Amy; his second, Self-Portrait with Expletives, was published in 2010 and dedicated to Joe and Hannah. His chapbook The Wanting soon appeared, rendering the imagined life of a scarred Vietnam vet. In 2021, his third full volume of poems, The Consecrations, was published by Stephen F. Austin University Press.

Having graduated from City College of New York, Joe came back West, where he’s currently a teacher and a visual artist in Southern California. A Barnard graduate, Hannah returned to the left coast as well, where she’s a therapist in Los Angeles. Kevin savors the amused—or, more accurately, bemused—smiles they still offer up to him when they visit.

Heraclitus wrote, “All things flow, nothing abides.” And once, after a no-way-in-hell come-from-behind win, the pitcher on his father’s mythic softball team said, “I’m tellin’ ya, I don’t know from nothin’.”

The fluid replaces the certain. Though fate may love a number, Kevin figures the number probably means little.… We’re not here for long and we don’t know from nothin’. It’s the family, friends, and students that amp the day. And, occasionally, the good line that finds the page we’re writing.